NaNo Update: Science Santa!

My NaNoWriMo word count reached 39,260 as Thanksgiving ticked over into Black Friday. Almost up to par.

And my Rocket Hub dashboard shows that I've funded four #SciFund projects, but there are more. The discrepancy has to do with my credit card company putting a freeze on my account because, well, they weren't used to seeing me click on the same kind of button that many times. So far as I know, that end of it has been resolved. Once the rest follows, I'll resume my holiday shopping!

Really, go check out the projects. If you want to inspire someone's scientific curiosity, here's your chance to touch base with researchers working on the front lines, doing innovative stuff. And as much as I love the companies from which I've bought things like our little Astroscan telescope, or the gyroscope I photographed for my chapbook of science poems, those things are mass-produced, ready-made products.

They're neat and all that, but they're not personal.

Every thank-you written on a postcard -- from places like St. Petersburg (in Russia, not Florida!) or South Africa or French Polynesia or Tel-Aviv -- or on a Gingko leaf (as Goethe used to do, when writing to his close friends) -- is unique. Every sample of data -- an autographed copy of a notebook page or handwritten mathematics from the research or handwritten field notes -- is a small piece in a grand adventure.

Want a paperweight or jewelry made from a cast-off crayfish claw? How about an alligator foot mold? Or a personalized Roman skull card? How about a bottle of wine that you can't get in any liquor store? Or a T-shirt print in high-res, living color of two algae in flagrante delicto? (Look at this picture; it's gorgeous. If you didn't know ahead of time, would you know what it was? Need a good guessing game for the holidays?) How about a unique DNA sequence from an animal being studied in the field? How about having a specimen named after you?

How about unique, woodturned art made by the scientist? Or a replica of models used in flow tank studies? How about stationery made from elephant poo? Or an acknowledgement in a presentation? Or a personalized kit for doing your own experiment? (Acknowledgements, copies of the research, and special access to progress reports are shared by several projects. Several high-end gifts include personal presentations and field tours.)

Holiday stress wearing you out? There's a virtual rainforest experience for that.

The swag is great in and of itself and there's something for every budget (I haven't covered all the projects here, not even close), but that's just one layer of the magic.

Back in December 2006, I had volunteered at a paleontological dig here in Florida, called the Tapir Challenge. Part 4 of my 4-part report is here, with a photo of the sea urchin spine I'd found. It had nothing to do with what we were looking for, but I was told that the quarry where we worked was full of them.

Then I was told I could take it home with me. And then I was told that it was probably 30 to 40 million years old. I was holding it in the palm of my hand. (Never mind that I had burned much older fossil fuels to get to the dig site. That was different.)

If someone my age gets all goose-pimply from that, imagine what a kid would feel. Now imagine a kid holding a souvenir from fresh, spanking, brand new science in the making, from a researcher who's breaking new ground.

But what about scientific inquiries that come to dead ends, as many do?

I could bust open a mess of incandescent light bulbs and pull out a filament like the one that had finally worked for Edison. I think of all the incandescent light bulbs in the world, especially prior to the changeover to fluorescents.

But what about the filament designs that didn't work? How common are those light bulbs now? Moreover, those filaments had been Edison's teachers. So had his early inventions, including his vote-recording machine, a disaster for being too far ahead of its time. When he lost the faith of his investors and his own funding was in peril, those failures had driven him on.

That makes them magic, too. Regardless of an experiment's outcome, it advances knowledge. That makes it pioneering work.

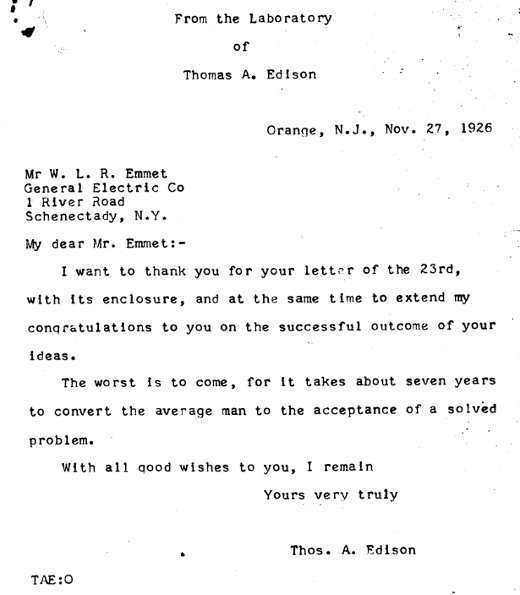

Speaking of thank-you letters from scientists...

Oh, wait -- Edison was a success by then. How about this one?

It reads, "Your favor of the 19th was duly received. The megaphone is not yet completed and I am quite unable to say when it will be as at present I am busily engaged on the electric light."

Who knew?

Who knows?

Want a taste of what Edison's passion and dogged determination felt like in the face of unknowns and uncertainties?

Here's your chance.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home